Chapters one-four

Section 1: Chapters One - Four

Flood states that in 1970 census tract 2, located in a Bronx neighborhood known as Soundview, “held 836 residential and commercial buildings on P.14. By 1980, there were nine left. Statistically, it wasn’t even the most devastated area in the borough - that was tract 173 ...” Flood offers no authority for these statistics, which he repeats on P. 185.

Data from the U.S. census reports for 1970 and 1980 demonstrate that these assertions misrepresent the facts. If Flood drew his data from this source, the 836 figure represents housing units, not residential or commercial buildings. In addition, both the number of housing units and population in Soundview increased during that 10 year period. If 9 buildings were left standing in tract 2 in 1980, where did the 3376 residents live? In addition, tract 2, is in Community District 9 and is not considered part of the South Bronx.

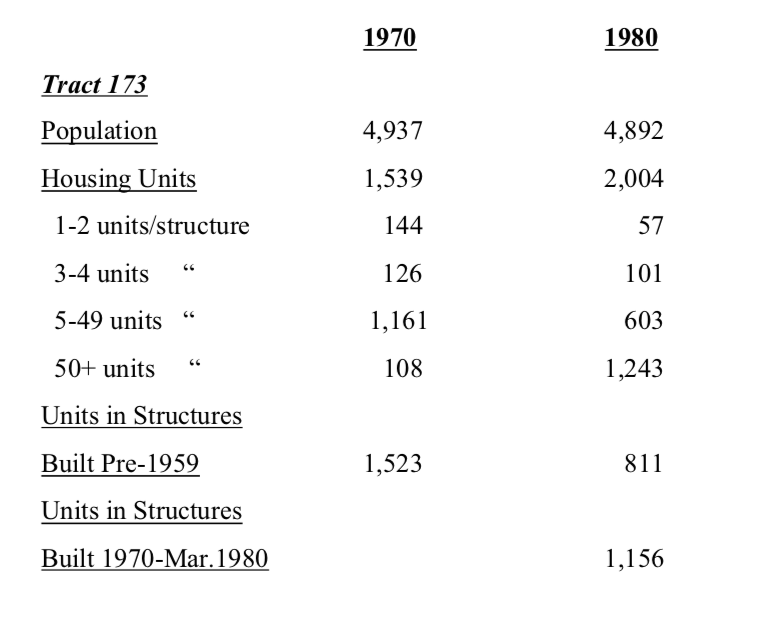

While we know residential housing units were lost to fire or abandonment during the period between censuses, it is impossible to determine from census data the number of structures that were lost because the census doesn’t track residential structures beyond noting the number of housing units that were located in structures built within particular time frames. For example, from the census we know that in census tract 173, most of the more than 1100 housing units lost between 1970 and 1980 were in structures built prior to1949 and during the same period some 1500 units were built. Just as the census doesn’t track residential buildings, it doesn’t track commercial buildings. Where Flood got his figures is unclear.

Cumulatively, between 1970 and 1980, New York City lost 823,000 residents; nearly 303,000 of those were Bronx residents. As a point of information, the Bronx began to lose population between 1950 and 1960, followed by an uptick during the1960s.

Another point worth noting is that the census data demonstrate that during the fire crisis, housing stock continued to be built throughout the City. According to the 1980 Census, the Bronx consisted of 340 tracts, not 289 as Flood asserts

P. 18 - Flood relies upon percentages to demonstrate that the arson rate in the city was never significant - ranging from < 1% in the ‘50s to <7% in the late ‘70s. But 7% of what? The total number of runs? All fires? Structural fires? Or fires determined to be “suspicious” or “incendiary”?

Not all fires believed to be incendiary were investigated as such. In a 1977 article Flood cites, Chief Francis Cruthers estimated that 25-40% of structural fires were incendiary and would be so identified if fire marshals investigated them all. He went on to say that of the number of investigated fires, 3600 - 4600 each year from 1972 through 1977 were determined to have involved arson. In 1977, structural fires totaled nearly 51,000. Using Chief Cruthers’ estimate, between 12,750 and 20,400 fires were incendiary. See New York Times, 6.16.77 cited P. 305n.

Later in the book, Flood first criticizes O’Hagan for reducing fire marshals when there was a “slight uptick” in arson and then he faults O’Hagan for starting marshal street patrols in 1977. P. 22, 192, 247. This pattern of criticizing both sides of management (without cited authority). Of those, 206 recorded stable or an increased number of housing units. One hundred thirty-four recorded reductions in housing units; 82 of those tracts had been specially designated during the 1970 census as comprising 10 low-income neighborhoods. Thirty-eight of the 134 tracts, notably in the South Bronx’s community districts, lost at least half of their housing units. The point is that the story of the destruction of housing and commercial stock in New York is more complex than Flood would have the reader believe. The tables below further illustrate that point as it is reflected in tracts 2 and 173. See United States Census 1970 and 1980, Tables H-1, H-2, H-7, and Documents relating to Bronx neighborhoods designated as ‘low-income’. See also the discussion on P.8.

(without cited authority). Of those, 206 recorded stable or an increased number of housing units. One hundred thirty-four recorded reductions in housing units; 82 of those tracts had been specially designated during the 1970 census as comprising 10 low-income neighborhoods. Thirty-eight of the 134 tracts, notably in the South Bronx’s community districts, lost at least half of their housing units. The point is that the story of the destruction of housing and commercial stock in New York is more complex than Flood would have the reader believe. The tables below further illustrate that point as it is reflected in tracts 2 and 173. See United States Census 1970 and 1980, Tables H-1, H-2, H-7, and Documents relating to Bronx neighborhoods designated as ‘low-income’. See also the discussion on P.8.

Tract 2

Tract 173

Not all fires believed to be incendiary were investigated as such. In a 1977 article Flood cites, Chief Francis Cruthers estimated that 25-40% of structural fires were incendiary and would be so identified if fire marshals investigated them all. He went on to say that of the number of investigated fires, 3600 - 4600 each year from 1972 through 1977 were determined to have involved arson. In 1977, structural fires totaled nearly 51,000. Using Chief Cruthers’ estimate, between 12,750 and 20,400 fires were incendiary. See New York Times, 6.16.77 cited P. 305.

Later in the book, Flood first criticizes O’Hagan for reducing fire marshals when there was a “slight uptick” in arson and then he faults O’Hagan for starting marshal street patrols in 1977. P. 22, 192, 247. This pattern of criticizing both sides of management action is consistent throughout the book, as pointed out below.

The City developed several initiatives to reduce arson, including two programs

O’Hagan helped inaugurate: liens imposed by the City on the insurance proceeds paid to a landlord following an arson and the use of auxiliary police officers to monitor alarm boxes from which false alarms frequently were transmitted. See Letters from Commissioner Robert O. Lowery to Mayor John V. Lindsay, 11.28.1972., 1.24.1973. Flood’s treatment of the role arson played in the destruction of housing and commercial properties is emblematic of the superficial analysis he brings to his thesis as a whole.

P. 18 - Flood quotes former Fire Commissioner Thomas von Essen about firefighting in the Bronx, “You know, in some ways the job became easier after 1975 or so, because even though there were all those fires, they were mostly in abandoned buildings.”

During the 1960s through 1970s, by some estimates, the South Bronx lost 40% of its residential and commercial buildings through fire, abandonment and demolition. That said, Von Essen is wrong. The table below, based upon the 1975 through 1978 Annual Reports, which Flood cites, demonstrates that fires in occupied buildings substantially exceeded those in fully vacant or partly vacant and deteriorating buildings.

*FD statistical categories changed these years.

P. 19 - 22 - Flood argues that during the 1970s, when alarms and fires hit record highs, 34 of the City’s busiest units were closed in high fire activity neighborhoods. Later in the book he focuses on the 12 engine and ladder companies that constituted the second sections - backup units designed to relieve primary units that were overextended in responding to alarms. He maintains that these companies were selected because they were located in poor neighborhoods, to facilitate slum clearance and consequent re-development and lacked the political clout to fight the closures. Reducing the level of fire service in those neighborhoods doomed them to destruction. P. 176, 179, 217, 224, 244.

Throughout the book, much of Flood’s discussion of the Fire Department units is confusing. The Appendix consists of a list of company openings, disbandings and reorganizations from 1965 through 1977 that facilitates understanding Flood’s assertions. It is first organized by borough and year. In addition, because the bulk of the Department’s changes occurred in 1972, 1974 and 1975, the information is presented in a second format, organized by year. The list is based upon a publicly available historical list of all the companies and units. See www.nyfd.com Also included is a city-wide map of each company’s location.

From 1965-1977, the Bronx gained 10 companies and lost 5, Brooklyn gained 8 and lost 8, Manhattan gained 2 and lost 9, Queens gained none and lost 4, and Staten Island gained 1 and lost 2 Overall, the department opened 23 and disbanded 28 companies. In addition, 25 special units were opened and 45 were disbanded. These special units included fireboats, an air tank refill unit, a field communications unit, the TCUs (tactical control units), and squads (units that combined an engine with a ladder). To put the loss of companies in perspective, during the fiscal crisis as the department’s labor force was reduced by 19%, fire fighting companies were reduced by only 7% as a result of management initiatives to minimize the negative impact of the crisis on fire protection levels. See Models in the Policy Process, Greenberger; Unofficial List of Fire Units, www.fdny.com. This unofficial list is interesting for another reason: it demonstrates that during the Department’s long history companies were frequently organized, disbanded, relocated and re-organized to meet the City’s needs. The list also illustrates that during this period no fewer than 37 companies were relocated to new or renovated quarters, changes that themselves altered the response times throughout the City. .

De-constructing Flood’s evidence in support of the thesis reveals it to be a game of smoke and mirrors. The 12 units he cites constituted less than 4% of the 375 engine and ladder companies, excluding some 90 special units. Of the 12 companies, 7 were in the Bronx, 3 in Brooklyn and 2 in Manhattan. Seven were truly closed - i.e., disbanded, not re-located or otherwise re-deployed. In 1972, one company was closed (Brooklyn, E 217-2). In 1974, six others were closed (Bronx: E 50-2, L 17-2, E 41-2; Brooklyn: E 103-2; Manhattan: E 91-2, L 26-2).

The remaining 5 units were not closed but re-deployed elsewhere within their respective boroughs (Bronx: E 46-2, E 85, E 88-2, L 27-2; Brooklyn E 233-2). Specifically, in 1969, E 46-2 was disbanded to organize E 88-2. Three years later, E 88-2 was disbanded to organize E 72 which was never disbanded in the 1970s. Another example is L 27-2. In 1972, that unit was disbanded to organize L 58 - at the same address. Similarly, E 82 and E 85 were located at the same address from 1967 until 1971 when E 85 was re-located 4 blocks away with a TCU (tactical control unit). E 85's workload at its new location on Boston Road was sufficient to warrant assigning the newly formed L 59 to that address in 1972. And, E 233-2 was re-organized as L 176 and relocated to Rockaway Ave., also in Brooklyn. Only E 72 was re-located more than one mile from the unit’s prior location; the other re-organized units were located no more than 3⁄4 mile from the prior location. Flood makes it sound as if each of the company changes, with the exception of E 46's re-deployment at E 88-2, removed all the fire resources rather than re-locating half the resources. A look at the map illustrates that company assignments in New York’s poor neighborhoods were dense and proximate to the high activity areas.

The Fire Department’s rationale for selecting the units closed or moved in 1972 and 1974 and the measures taken to mitigate the negative effects of the closings were set forth in the Fire Bell Club News Notes, press accounts at the time, and publicly available court records. See Maye v. Lindsay, 72 Civ 4912 (S.D.N.Y.1972); Lowery Affidavit; Towns v Beame, 74 Civ 5411 (S.D.N.Y. 1974). O’Hagan Affidavit, Bishop Testimony. These mitigation strategies and additional flaws in Flood’s treatment of the second sections are discussed below at P. 23 - 26, 29 - 31, 37.

Flood’s analysis is flawed in several other important respects. In further support of his thesis, to demonstrate that the second section changes adversely impacted fire protection in the South Bronx, Harlem and Brooklyn, Flood recites in a cursory way the increased number of workers the remaining units handled following the withdrawal of the backup unit. A discussion of “workers’ as a poor measure of workload begins on P. 28.

P. 21 - Flood claims that while the national fire fatality rate fell 40% during O’Hagan’s 14-year tenure, NYC’s fire fatality rate doubled. P. 284. He cites for this statement the National Research Council’s Committee on Fire Toxicology report “Fire and Smoke: Understanding the Hazards”, a report on the degree to which fire deaths are caused by materials (i.e., plastic, etc.) that ignite rapidly or generate toxic fumes. The text of the reference refers only to the national rate; there’s no mention of the New York rate. Moreover, the national rate quoted therein is adjusted for population and omits fire- related transportation deaths.

It is impossible to determine how Flood calculated the figure he ascribes to New York. Using the grossest of measurements, total city population divided by total civilian deaths, the rate might be said to have increased 61% from ˜23/M to ˜37/M - with no adjustment for population or omission of fire-related transportation deaths. Moreover, since the census is conducted only every 10 years, the population data used for this calculation is not accurate on a year to year basis. Flood’s reliance upon this calculation flies in the face of his position that fire resources should be allocated according to the intensity of fire activity. By distributing the risk evenly across population, Flood at least implicitly concedes that fire protection resources similarly should be evenly allocated across the population.

There are at least 4 other ratios involving civilian fatalities that measure fire fighting effectiveness: deaths per total number of fires, deaths per total number of serious fires (defined as an all-hands or greater alarm), fires in which a death occurred per total number of fires or serious fires. Using Flood’s preferred measurement - total fires, i.e., workers - the ratio ranges from 2.26deaths/1K to 2.23/1K. Per serious fires, the ratio ranges from 112deaths/1K to 63deaths/1K. If the ratio uses the number of fires in which a death occurred - i.e., in 1970, 310 deaths occurred in 245 fires - the ratio is even less.

It’s also worth noting that in 1970, the year civilian deaths peaked, the Fire Department’s manpower also peaked at 14,325 uniformed men. Conversely, in 1975, the year fires peaked and manpower hovered at 11,500, civilian deaths fell to 245 in 198 fires.

Two other analyses demonstrated that the fatality rate did not increase during that period. Analyses of the deaths that occurred in structural fires from 1967 - 1972 demonstrated that the ratio of deaths per structural fire did not increase during that time. See “Fire Casualities and Their Relation to Fire Company Response Distance and Demographic Factors”, Fire Technology, Vol. 12, No. 3 (1976), P. 193-203. This article explains in detail the difficulties in using civilian fatalities as a measure of relative risk across the City. Another study covering 1972 - 1978 showed a ratio of 0.0054, lower than the ratio of 0.0061 for the period 1958 - 1971. In addition, Deborah and Rodrick Wallaces’ work, which Flood cites, projected 340 civilian deaths for 1976. In truth, 289 civilians died in fires that year, a figure lower than the projection and perhaps a reflection of successful management techniques. See Management Science, supra, P. 429.

These studies also put in context Flood’s statement that the civilian death rate increased more than 100 percent “over the past few years.” P. 178. The point is that Flood’s grave thesis is based upon superficial, unsophisticated analysis.

Another number of interest is that from 1968 through 1978 firefighter deaths never exceeded 9 per year. That figure includes the firefighters lost at the Waldbaum’s fire.

Flood also asserts that civilian deaths were under reported because (1) the Fire Department didn’t include people who succumbed to their injuries subsequent to the fire and (2) deaths were often categorized as heart attacks or homicides to avoid being included in the count P. 246, 305. Flood provides not one example when either claim occurred. His account of the 1976 statistical error in counting civilian deaths does not address either of these serious assertions. P. 305. Moreover, his assertion that the calculation error was not corrected for many years is simply false. The news article Flood cites in the note is dated September 1977, nine months after the end of the year in which the error occurred.

According to material in the Lindsay archive, the chief in charge of the fire reported on victims taken to the hospital and recorded deaths as they occurred. See Lindsay Archive, FDNY Statement 9.23.66.

Deaths often occurred due to delay in discovering and reporting the fire, and some fire-related deaths occurred under circumstances where the Fire Department was not even called. The Annual Reports explain the contexts in which civilian deaths occurred. For example, of the 196 deaths in 1965, 67 were categorized as having occurred due to carelessness; 32 involved children who were left alone. Look also at the 1970 statistics, the year civilian deaths peaked at 310 in 245 fires. Ninety-three deaths related to smoking; 38 involved children playing with matches; 27 involved open flames. 21 of the 62 children who died had been left alone. One hundred ninety-four of the 245 fires were in dwellings; 214 people died in those fires. Ninety-six deaths occurred in non-structural fires. The following chart places the 1970 civilian deaths in context:

P. 22. Flood maintains not enough was spent on the purchase and repair of equipment or the maintenance of hydrants. P. 121, 192, 220, 224, 245, 304n.

Each annual report details expenditures made on repairs. On average 1000+ shop and 7000 - 7800 field repairs of apparatus occurred each year.

The reports also describe equipment deliveries, orders and capital allocations. For example, in 1969 newly delivered equipment included 40 new pumping engines, 4 conventional aerial ladders, 2 rear mount aerial ladders, 4 tower ladders. The capital allocation for the following FY was $5.6M. Eighty pumping engines, 21 aerial ladders and 6 tower ladders had been ordered for delivery in 1970.

In eight years, department-wide, the equipment replacement cycle was reduced from 30 to 10 years. See Annual Reports and Letter from Mayor John V. Lindsay Letter to Robert O. Lowery, 9.11.73.

Even at the height of the fiscal crisis, 1975, more than $8M was allocated for equipment.

Non-functioning hydrants posed a vexing problem. To address it in a way that enabled firefighters to access broken/distant/low water pressure hydrants, the 1969 Annual Report reports the development of in-line pumping techniques and novel ways to lay hose in the fire truck. See P. 9-10. The E.P.A Department of Water Resources bore primary responsibility for maintaining fire hydrants.

In January 1970, , Mayor Lindsay sent a memo to the relevant department heads directing that the defective hydrant problem be addressed. By letter dated, January 20th, the EPA responded with its plan. See Memorandum from Mayor John V. Lindsay to Budget Director Frederick O’R. Hayes et al., 1.5.1970; Letter from Maurice M. Feldman, E.P.A.. to Mayor John V. Lindsay, 1.20.1970.

P. 24 - Flood writes, “ And so, for all the paradoxes inherent in closing busy fire stations while the neighborhoods around them burned, the greatest irony would be the who and the how and the why of these closings: John Lindsay, an ardent supporter of civil rights .... overseeing policies that burned down New York’s black and Puerto Rican ghettos; John O’Hagan, the most influential and forward looking fire chief in the country, gutting his own department; and the RAND Corporation, an organization devoted to logic and rationality, recommending the most illogical of policies.”

Each of these notions makes for poetic rhetoric but each is a false paradox not supported by fact.

P. 30, 34, 35 - Noting that O’Hagan served in WWII as a paratrooper with the 11th Airborne Division, Flood describes an episode of Japanese retaliation that he assumes O’Hagan witnessed and goes on to imagine how O’Hagan recounted those wartime experiences over the years. References to O’Hagan’s reticence in talking about the war, thick beard and skin condition are accurate. The rest, uncited, is made of whole cloth.

P. 30, 33 - Flood fictionalizes O’Hagan throughout the book. One example is on P. 30. Commenting on what he supposes was O’Hagan’s elementary school education in the Catholic catechism, Flood writes, “The second advantage of the Catechism was that it contained, conveniently organized by topic and theme, hundreds of complicated questions about society, morality, and religion, all answered in succinct, lucid prose ... It didn’t inspire abstract poetry, but as a model for how to organize subjects and synthesize complex ideas into clear writing, it was hard to beat. A knack for math and science made O’Hagan a natural test-taker, but the writing skills he developed helped translate that analytic aptitude into his greatest intellectual strength, the ability to turn abstract quantifications into useful concepts, to give numbers the power of narrative.”

This is almost too silly to address, except that it illustrates Flood’s effort to create a character he later fashions as the malefactor for his own narrative. Need it even be said that math and science skills do not a successful test-taker, analyst or writer make. As for writing skills, no one who read O’Hagan’s articles or book on high-rise fires would think he had a powerful narrative writing style. See O’Hagan article cited on P. 19.

P. 40 - Flood writes, “O’Hagan was cautious in his dealings with the real estate industry, speaking to them not in the blunt terminology of a fire chief looking to save lives, but that of a businessman looking to limit liabilities.”

It’s hard to tell what this sentence means. Loss of life and property have gone hand in hand from the time each insurance company employed its own formal fire brigades. The key to the sentence seems to be the terms “cautious”, “blunt” and “businessman” to convey some negative impression. In addition, the assertion is unsupported by an authoritative source. Flood uses this section to set the stage for his later assertion that O’Hagan facilitated destruction of property to assist unidentified real estate interests. Flood also overlooks the fact that many New York fire departments began as arms of insurance companies that protected the neighborhood insureds from fire loss.

P. 65 -70 - Flood notes with approval a variety of innovations that improved the Fire Department’s operations, including staggering unit assignments according to where the data demonstrated fire activity had increased. Later in the book these are the very innovations he criticizes.

He also writes, “O’Hagan’s greatest ambition went beyond new technology and the day-to- day running of the department ... A professionalized, objective way of doing business that O’Hagan thought could be applied not only to the FDNY but to bureaucracies everywhere ... O’Hagan’s goal of reshaping the civil service far outstripped his mandate as the second in command of a single municipal department, but the chief had never fallen short of an overambitious dream before.”

This is another of the innumerable sections in the book where Flood spins speculation, supposition and hyperbole to build his case. The City turned to RAND because, as Flood acknowledges on P. 69, the traditional ways of assigning staff and allocating companies no longer worked as the Department confronted the quickly escalating demands for fire protection throughout the City. As one RAND report put it, “In 1968, ... the Department was faced with unprecedented demands for its services. ... At 8 o’clock on a summer evening in the Bronx ... typically about half the fire companies .... were unavailable because they were already busy... Communications channels and dispatching centers were clogged with alarms - it was not unusual during peak evenings for it to take five minutes or more to dispatch units to an alarm...” See Improving the Deployment of New York City Fire Companies, (1974), P. 1.

From that beginning, to ascribe to O’Hagan the ambition of extending RAND practices across government is unfounded. It is though an assertion repeated on P. 222. The Mayor, not O’Hagan, engaged RAND to work on a number of projects, initially with four municipal agencies. The decision had nothing to do with one chief down many rungs on the city hierarchy ladder. In the last sentence of this chapter Flood further confuses things by seeming to ascribe the ambition he assigned to O’Hagan now to Lindsay, who at least had the authority to think in those terms.